It slipped out with a low-key press release.

The University of Tasmania’s Climate Futures Group has recently released a seminal document (funded by Wine Australia) that maps out the future climate of Australia’s wine regions – and it is scary as hell.

It’s a benchmark ‘Climate Atlas’ which looks at climate indices (heat accumulation, rainfall, seasonal variations) and then correlates it against the predicted effects of climate change – and Wine Australia should be commended for backing it.

But it doesn’t make for good reading…

The Losers

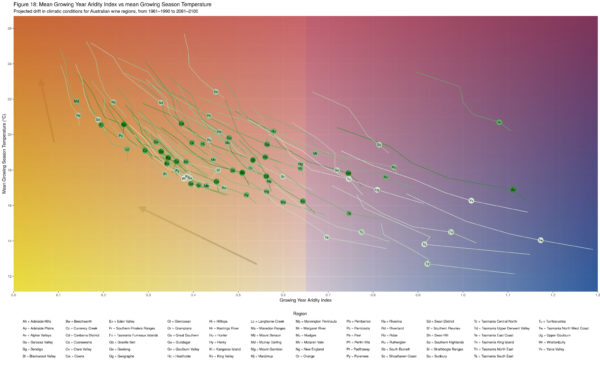

In particular, this graph (and I apologise for reprinting to the authors for reprinting, full document can be found online here) gives possible indications for what will happen by 2100 in some of our key regions, with predictions for increases in aridity and mean growing season changes (click the image for a larger size).

According to the calculations, a region like the Barossa will have a climate more like the NSW Riverina come 2100 – much drier, much hotter. By contrast, the Riverland will become a challenging place to grow winegrapes at all…

This handy infographic paints the picture for all of Australia’s GIs, like this one for the Barossa.

Think that doesn’t mean much? Well consider this – that dry grown Barossa Shiraz you like so much? Bloody hard to manage in a climate like that, where the double attack of increased heat and increased aridity means that plants require more water and lose it faster. That means it is harder to grow anything without irrigation in lower rainfall areas.

Think that doesn’t mean much? Well consider this – that dry grown Barossa Shiraz you like so much? Bloody hard to manage in a climate like that, where the double attack of increased heat and increased aridity means that plants require more water and lose it faster. That means it is harder to grow anything without irrigation in lower rainfall areas.

What’s also fascinating is that rainfall patterns will change, with winter rain set to decrease in many regions, while growing season rainfall marginally increases. In some examples this is good, but for most GIs it poses some problems – for one, winter rain is useful as it boosts soil moisture levels during periods of decreased evaporation, while posing no disease risk to dormant vines. By contrast, growing season rainfall adds increased disease pressure and potentially increase vigour.

Further, the year 2100 Barossa climate will mean growing seasons are also pushed earlier, with grapes ripening in the heat of January instead of the cool evenings of March, which is generally considered less desirable for even ripening (and quality by extension). I can only imagine what will happen when the ‘new normal’ subtropical January storms hit those stressed grapes – it’s berry split city.

Aridity and increased temperature is just one element – we’re not even discussing smoke taint from increased bushfire risks. Or the challenges of berry damage from heatwaves, or indeed vine death if temperatures hit above 53C (which is very possible).

Of course, you can dismiss this Climate Atlas document as scaremongering. And I think the way the document is presented (with tricky to read graphs aplenty) is part of the reason why it has received limited attention, especially given how fragmented and perilously unprofitable the wine media is in Australia. But surely I’m not the only one reading documents like this and thinking ‘we’re all fucked?’ Admittedly with my dual environmental/wine background I’m a little more invested than most. But still, doesn’t it scare you to think that the wine regions you cherish so much might become non viable within this century?

Admittedly, I’m discounting the adaptability of grapevines, which are remarkably tolerant, still producing fruit even during extreme weather events. There was a very comprehensive study done in 2009 using Barossa Shiraz that examines resilience to heat and heatwaves, showing that vines are hardy and can cope with temperature variations. Worth a read if you have an hour or so (here).

It’s also important to acknowledge what this study serves to do – highlight the predicted challenges, so vignerons can adapt and change their practises with some hard data of what to expect.

Wine Australia General Manager RD&E Dr Liz Waters spells it out well in the press release, offering the document as a valuable resource to help the sector manage climate variability:

‘Extreme weather events have always posed a challenge for grapegrowers around the world and this new resource will help Australia’s growers to choose adaptive strategies tailored for the changes in their region based on inter-annual and decadal projections’, Dr Waters said.

The Winners

Oh and there are some (relative) winners from climate change too. Just like the vignerons of Switzerland, England and the Benelux nations who are suddenly more able to grow quality winegrapes, the wetter parts of Tasmania are (theoretically ) about to become much much more grapevine friendly. And some regions across the country will be less affected than others due to localised considerations (like the frosty parts of Tumbarumba).

Regardless, if you’re an Australian vigneron this Climate Atlas should instil fear into your world. By extension, it should remind all of us winelovers that climate change could – and will – pose an existential threat to Australian wine as we know it.

And we need, as a globe, to realise that a low emission future is the only future…

Help keep this site paywall free – donate here

Comment

Here here Andrew. Great and timely highlighting of this research.